|

330 GT Registry |

|

|

THE

A |

The 330 GT is not one of the more memorable supercars but it serves testimony to the fact that Ferrari produced the sensible as well as the seductive. David Vivian finds it an excellent GT |

Flicking through my coy of the illustrated Ferrari Buyer’s Guide, an invaluable floppy-backed reference book by the notoriously miserable Dean Batchelor who “lives in sunny southern California and owns three Ferraris”, I realise that there are at least 20 Ferraris whose looks I like less than those of the 1964 330 GT. If I actually liked the look of the 330 GT, this would be no big deal — and, let’s face it, who cares what I like anyway? But I don’t and therefore can only sit in wonder at the ugliness of some of the creations that bear Enzo’s surname. Admittedly, most of these were styled by Michelotti, whose masterwork was the Triumph Spitfire, but even the old maestro himself, Pininfarina, had a penchant for wheeling out the freaks when the mood struck.

If you aren’t already familiar with it, check out the Pininfarina Spyder of 1957— it looks like the aftermath of a crash between a TR3A and the Batmobile. Then there’s the incomparable Superfast II of 1960, which resembles nothing so much as what you’d imagine a frog that had swallowed a large bar of Camay to look like. Worse by far, however, is Michelotti’s extremely rare 340 America Turbolare, which Batchelor tactfully describes as “interesting” in his book. What he really means is “hideous”. Head on it could be a mechanical catfish with a brace, yawning. And that’s its best angle.

|

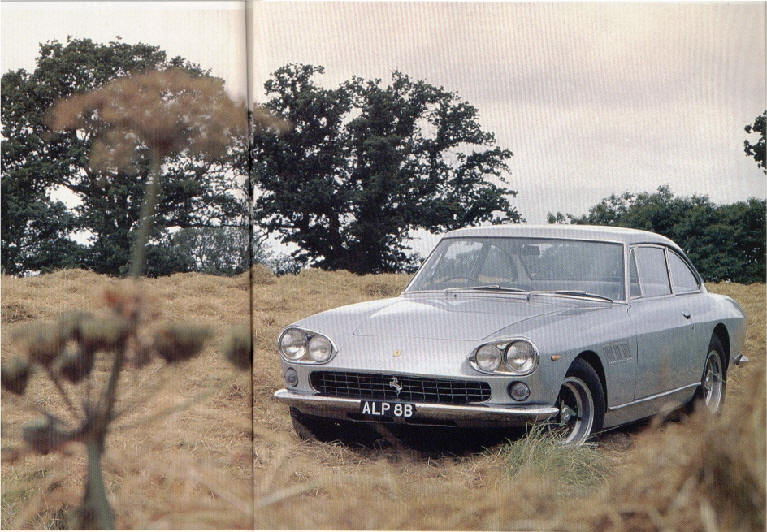

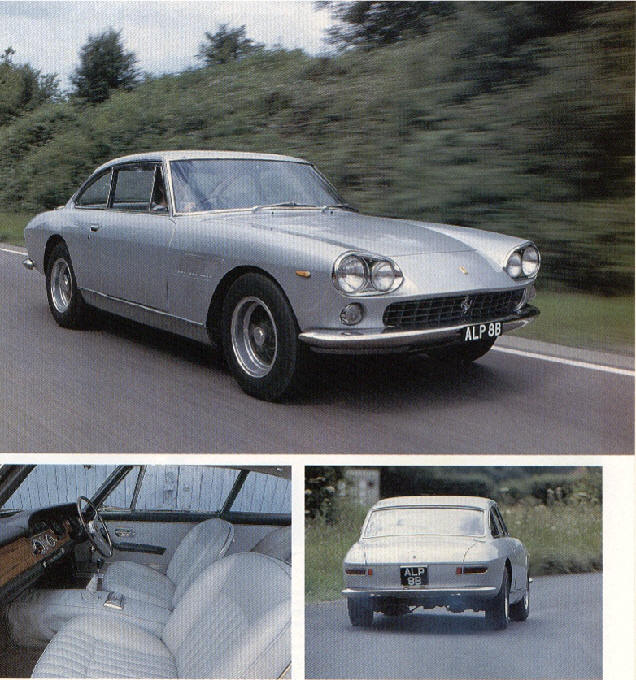

330 GT’s 3967cc boasts the two Ferrari V12 essentials: a broad torque spread and a fabulous sound at high revs. Interior looks makeshift and use of wood is unsuccessful but seats are good. Handling is neutral and the whole adds up to a true grand tourer in the ‘60s Ferrari tradition. Styling nose to tail ranges from aggressive to anodyne |

I’m tempted to go on but the point I’m trying to make is that it’s too easy to fall into the trap of believing that all Ferraris are unutterably beautiful, extremely fast, sexier than Uma Thurman, more enthralling to listen to than the LSO playing Mahler’s 9th and worth a mint. The sheer romance of the name tends to evoke an image amalgamated from the best bits — a dizzy, swirling montage of Dinos and Daytonas, GTCs and GTOs. In truth, however, the Maranello factory churned out the dire as well as the desirable, the mediocre as well as the magical and, what concerns us the sensible as well as the seductive.

Apart from the much later and somewhat overblown 400, the 330 GT is probably the most practical and pragmatic car ever to emerge from the Maranello stable. It superseded the largely unloved 250 GT — not the gorgeous Berlinetta but the staid and frumpy two-plus-two, a worthy enough tourer of limited charisma powered by a three-litre single-cam-per-bank V12 developing a fairly modest almost certainly optimistic) 240bhp at 7000rpm. Just how modest (or optimistic) be came apparent when American owners, their bulky steeds weakened further by anti-smog gear, started getting blown away by big cube domestic stock saloons and coupes never mind the E-types and DB of the day. Understandably, sales suffered.

The answer, as usual, was a larger engine, in this case a new Columbo-based 60deg V12. With bore and stroke dimensions of 77 and 71mm, the all-alloy unit displaced 3 967cc and developed a claimed 300bhp at 6600rpm and 2401b ft of torque at 3000rpm (compared with the 250’s relatively weedy 1841b ft at 5500rpm), outputs which looked as if they might be able to do something useful with a kerb weight of around 3200lb.

In its design, the engine conformed to the usual Ferrari architecture, the camshafts being driven by chains and the valves (two per cylinder) operated via roller-follower rockers. The crankshaft ran in seven bearings with the connecting rods coupled in pairs. Like the cylinder block, the crankcase was cast in silumin alloy while twin Marelli distributors driven from the back of the camshafts took care of the ignition. Three twin-choke Webers supplied the fuel.

Early 330 GTs used the 250’s even heavier body and were called 330 Americas, but Pininfarina had been on the case for some time and, in 1964, the bigger engine found its proper home. Only the general proportioning was similar, Pininfarina’s new GT looking smoother, more rounded and somehow less laboured than its predecessor almost bath tub BMW-esque at the rear. But the rear wasn’t the problem. The four headlamps, each pair set in a curious ovoid nacelle, were: they gave the nose, with its broad cheesecutter grille, a brutal appearance which seemed almost wholly at odds with the demure profile and anodyne tail toting its vestigial lamp clusters. The criticisms were duly noted and, in 1965, a ‘prettified’ 330 GT with single headlamps and simplified detailing replaced old four eyes. If it looked better at all it was only by being bland to the point of virtual anonymity and many ended up prefer ring the ‘Mk I’.

Either way, the important thing about the 330 GT wasn’t so much how it looked as what it did. From the performance point of view it did all right at least well enough for the Ferrari to be in with a shout of acquiring the ‘world’s fastest four-seater’ mantle, though when the American magazine Car and Driver put this to the test in March 1965 by facing off the Ferrari against a home-grown seven-litre Pontiac Catalina two-plus-two, in all matters acceleration the 330 GT was simply annihilated. But then if, as C&D seemed to be saying, the Pontiac was capable of 0-60mph it 3.9secs, 0-100mph in 12.0secs and the standing quarter in 13.8secs, it would have taken an F40 (still another 24 years away) to do much about it. Were American cars really that rapid and, if so, does anyone have a Catalina we can test, please?

Back to the 330 GT. According to most contemporary tests, it could sprint to 60mph in around 6.5secs, 100mph in 16secs and had a top speed in the region of 145mph. Give or take a few tenths and mph, that’s BMW M635 CSi performance, which is still considered a benchmark for GTs today. By all reasonable (Pontiac-free) standards, the Ferrari delivered. It had a five-speed gearbox with an overdriven top giving around 24mph/1000rpm and intermediate ratios spaced to allow 48, 72, 98 and 124mph at 6500rpm. Suspension was by wishbones and coils at the front and a live axle with half-elliptic leaf springs, radius rods and auxiliary coil springs at the rear.

Of the ZF worm-and-roller steering, Autosport’s Gregor Grant said back in 1964: “It was something of a surprise to learn that this was power assisted, for there was not the slightest trace of deadness, the wheel at all times feeling very much alive and entirely responsive.” Gregor was driving ALP 8B, the first of only 44 right-hand-drive 330 GTs to be brought over by Col Ronnie Hoare, then boss of Maranello Concessionaires. The car was dark blue and worth a little over £6000 at the time of that exclusive drive.

Today, it’s metallic silver and on sale for 49,950 — a modest sum for a clean 27-year- old Ferrari. I caught up with it at Eagle Racing in Chart Sutton, Kent, for a drive. It didn’t help my sense of perspective that I’d just stepped out of a six-litre, 160mph Mercedes S-class. The ‘big’ Ferrari felt roughly Escort-sized after the leviathan limo and its performance strangely restrained in the wake of the Mere’s neck-bending torque. But then the 330 GT was never intended to be a Daytona substitute. All it had to do was live up to a name that actually meant something in the ‘60s — grand tourer — and by all accounts it fulfilled that role with considerable flair.

Despite my earlier comments, this Ferrari looks all right in the flesh. It’s not the sort of shape that reprograms your metabolism and it’s debatable whether the aggressiveness of the front is preferable to the amorphousness of the back but, in profile, the super-slim cab in pillars and masterful proportioning suggest Pininfarina in good form and that means elegance of a high order. Alas, the same cannot be said of the interior which, while spacious enough to seat four adults at a pinch, looks woefully makeshift, even by exoticar standards.

Immediately likeable are the comfortable, low-slung seats, the exquisite thin wood- rimmed three-spoke wheel and instruments so big you can’t help but notice them. The same goes for the chunky controls, which contrast intriguingly with the slim column stalks. The rest of the facia, however, is a disaster and looks as if it was knocked together from a 50- pence job lot of timber-yard off-cuts. Henry from Eagle Racing had similar thoughts when he saw his first 330 GT, but he’s seen half a dozen now and they’re all the same.

But if ever there was a car you shouldn’t judge on the basis of first impressions, this Ferrari is it. From cold, the gearbox is graunchy, the engine clattery and lethargic, the steering inert and the brakes wooden. It doesn’t take a few miles for these effects to wear off but a good 10. Slowly the recalcitrant shift eases; then it becomes so light you can push it around with your fingers. It’s a delight.

You notice that the valve gear rattle has subsided and, on a light throttle, the engine is almost inaudible. Squeeze the pedal, though, and there are a couple of surprises. First, the torque: the four-litre lump is beautifully flexible, pulling cleanly from just under a thousand revs and strongly from about two-and-a-half. Second, the sound: undeniably subdued for a 12-cylinder Ferrari, all the magic ingredients are there — the soft bellow of the exhaust, the guttural gurgle of the carburetion and, above 4000rpm, a rising howl that animates the hair on the back of your neck.

That steering, which seemed so lifeless, still doesn’t appear to have the precision Gregor wrote of but it sends back enough clues about the road surface for the driver to quickly feel confident and is decently responsive on lock. The 330 corners with a sense of benign stability, understeering up to a point before settling into a comfortable neutrality. The chassis feels soft and woolly by modern sports car standards and rides poorly at low speed. Grip is better than fair, though, and the Ferrari’s balance and poise are still a class act.

I

suspect that a leisurely drive to Provence would cement the relationship. For

obvious reasons I can’t oblige, but someone should. I get the feeling that the

330 GT has seen enough of the leafy lanes of Kent.

Eagle Racing can be contacted on 0622 843312

7 August 1991 AUTOCAR & MOTOR

Copyright Autocar and Motor 1991.

Published with permission from Autocar.