| 330 GT Registry |  |

UNKNOWN PLEASURES

Richard Heseltine asks: can Jensen’s hybrid compete with a pedigree Ferrari?

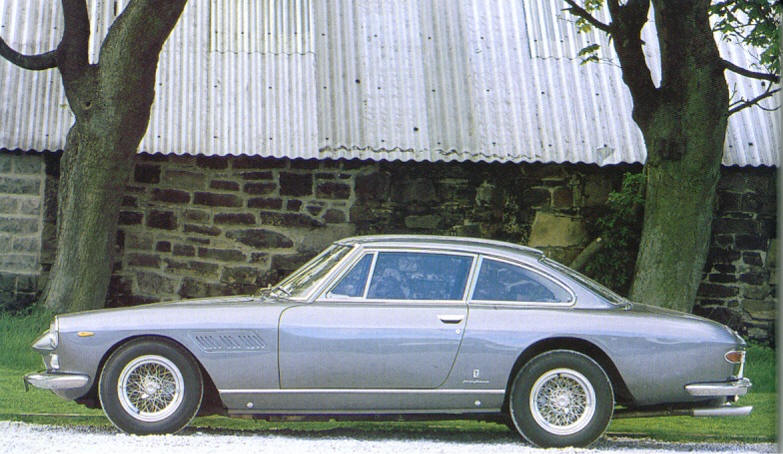

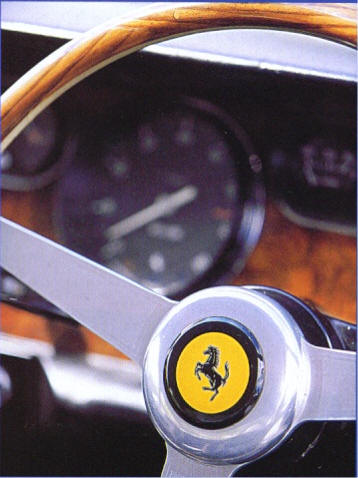

| Above: graceful 330’s lines were work of American Tom Tjaarda, then the rising star at Pininfarina; its trademark script is on the rear flanks (right). Below: beautifully trimmed leather and wood-veneered cabin is Ferrari’s finest study in understatement. |  |

| |

On paper, it seemed a mismatch. Saying it out loud failed to convince: it still smacked of inequality. Jensen Interceptor vs. Ferrari 330GT 2+2—the plucky West Midlands underdog takes on the Modena purebred. Not a natural for pay per view. But why? Three words: Hybrid. Crossbreed. Mongrel. The marriage of proletarian American V8 muscle and European design flair has long been viewed by right thinkers as being little more than a sham. So, despite the two being closely matched for pace and featuring dazzling Latin couturiers’ outlines, the Jensen is always on to a loser by dint of having a proprietary engine.

That’s one theory. Truth is, Ferrari is the unbowed top banana of exotica. It doesn’t matter that the marque has latterly squandered its reputation for cash by merchandising the name to within an inch of its life. Ferrari has the lineage, the race wins and the kudos.

Jensen, however, does not. Thing is, even within Maranello lore, there’s a pecking order and the GT has since become the lesser cousin of its other ‘60s offerings. Aside, that is, from the 250GTE that it replaced — perhaps the most underappreciated Ferrari of them all.

Presented during the traditional first press conference of the year at the Modena factory on January 11, 1964, this new coupé’s handsome profile was once again the work of Pininfarina — or rather the firm’s rising star Tom Tjaarda. Its engine (type 209) was derivative of the 400 SuperAmerica item, sharing its 3967cc displacement, although the Lampredi V12 was lengthened in order to improve the circulation of water in the block while allowing better positioning of the spark plugs.

The 2+2’s chassis was typical Ferrari — a perimeter frame comprising oval-section tubes, the engine held in place by four mounts. Wheelbase was increased over its predecessor by 2in, while sharing much of its coils and wishbones front/live axle rear suspension but with Koni adjustable dampers.

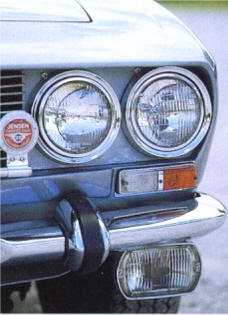

Though praised for its dynamics, the 330 wasn’t beyond criticism, and the controversial quad headlight arrangement came in for a mauling. The following year, it was restyled (much to Tjaarda's disgust) with two lamps in place of four, and the traditional Borrani wire wheels became an option. And so it remained until ‘67 when the 365GT 2+2 arrived at the Paris Salon, signalling its demise. Around 1080 were built in four years.

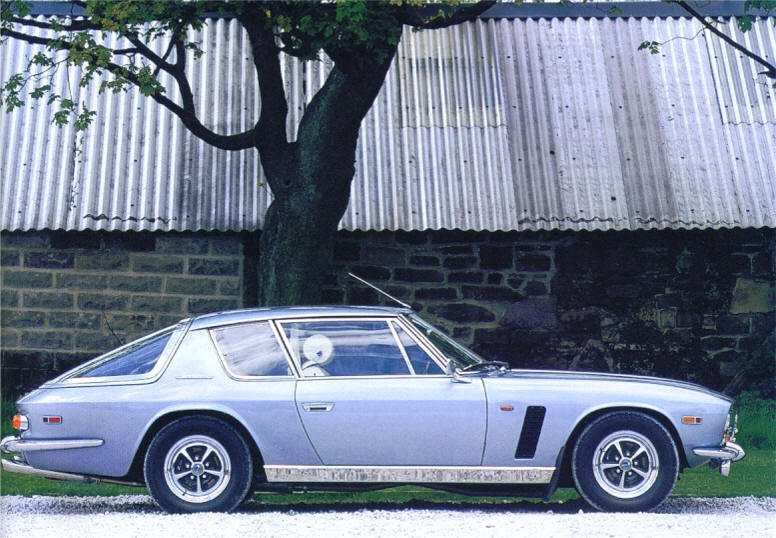

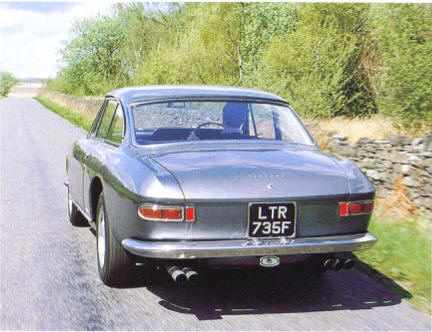

Meanwhile, in West Bromwich, Jensen had laboured for 32 years — 1935 to 1967 to get into four figures. The Interceptor was to change all that. Ushered in at the 1966 Earls Court Motor Show this was to be the first offering from the Midlands minnow not to be styled in-house. After investigating the Italian carrozzeria, a Vignale design was chosen with Touring of Milan providing the Superleggera body construction tooling. Ironically for a firm steeped in coachbuilding, Jensen commissioned the first handful of shells to be made in Italy (apparently identifiable from UK cars by deeper side air vents and odd hits of timber in the door frames) in an effort to speed up the transition from prototype to fall production. Making things a little easier, the Interceptor was essentially a reclothing exercise, the existing C-V8’s massive steel box-section chassis being retained largely unaltered, with a steel skeletal structure welded to it: at 36971b, the newcomer was 11 per cent heavier. Power, as before, came from Chrysler’s iron-block 6276cc V8, meaning 325bhp (against the Ferrari’s optimistic 300) and a colossal 4251b ft of torque. Power was fed to the rear wheels through a Powr-Lok limited slip differential, four-wheel Dunlop discs (as on the 330) being another carry-over from the C-V8. It was an instant success, Jensen turning out 1074 Series 1 cars in only four years, just 24 of them with manual gearboxes. The MkII from ‘69 featured revised suspension and a new fascia; the MkIII followed two years later, with vented discs and cast-alloy wheels, the 7.2-litre SP arriving concurrently. Then there was the technical tour de force but costly FF 4x4 trailblazer, handsome convertible and gawky Panther-devised fixed-head coupé. Even after the firm crashed in 1976, the Interceptor wouldn’t lay down and die: it made a brief and ill-starred comeback during the late ‘80s, one of the penny numbers S4s featuring in the is woeful The Saint TV movies of the period. | ||||

|

Yet, while later iterations would be more polished performers, none had the delicacy of line of the original: no chintzy grille, lumpen tail-light clusters or flash rims. The Series 1 is a good-looking machine that, despite its Latin heritage, still manages to appear English. Certainly the elevated bonnet line and bluff frontage has a touch of the later Astons to it, although the rear is a shameless crib of Giugiaro’s ‘63 Testudo design study (and could have inspired the AMC Pacer). Hunkered down on polished Rostyles it looks the part. In true ‘60s Pininfarina fashion, the 330 exudes both delicacy and muscularity. The overall silhouette is elegant despite the large rear overhang, the slight nose-down rake and those quad headlights offering a confrontational attitude. It’s a car that looks better in the metal than photographs and in a dark colour: anything but red. This example, first owned by former Ecurie Ecosse man Jimmy Stewart, brother of Fl legend Jackie, appears suitably muted in gunmetal. Once inside, the Ferrari offers all the tactile pleasures you would expect: it really is lovely about as understated as any Ferrari’s cabin could be and free of later, customer-driven clichés. Ahead, the large Nardi wheel fronts the customary polished wooden dash, the classic white-on-black Veglia instrumentation being easy to read. Soft, aged leather embraces the seats and door panels, additional furniture being sparse but stylish, not least the heavily spring-loaded chrome ashtray above the transmission tunnel. | ||||

| FERRARI 330GT 2+2 Engine front-mounted all-alloy single ohc per bank 3967cc V12, fed by three Weber 40 DCZ/6 carburettors Transmission four-speed manual (five-speed from mid-’65) Max power 300bhp @ 7000rpm Max torque 288lb ft @5000rpm Construction tubular perimeter frame chassis with steel body Suspension: front independent, by double wishbones, coil springs, Koni adjustable telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar Rear live axle, radius rods, semi-elliptic leaf springs, auxiliary coil springs, Koni adjustable telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar Steering ZF worm and roller Brakes dual-circuit Dunlop discs all round Length 15ft 9½in Width 5ft 7½in Height 4ft 5½in Wheelbase 8ft 8in Weight 3040lb 0-60mph 7.4 secs Top speed 144mph Price new £6217 Price now £25,000 (good) |  |

|

Step aboard the Interceptor and the seating position is dictated by the slightly offset pedals. The separate hooded cowls for the speedo, and the centre console with its myriad toggle switches and idiot lights, makes for a jet-set ambience: you cannot help but smile at the view. Additional bonus points are won by the seats which are surprisingly hard-backed with excellent lumbar support, something lacking in the 330. Yet, unlike the Maranello machine, the Interceptor is in no way a true two-plus-two. Even the stumpiest of children would be suffering pins and needles after five minutes in the back. Still, as befits a genuine gran turismo, there’s a 16 cu ft boot — bigger than its rival's.

|   |

| JENSEN INTERCEPTOR SERIES I Engine front-mounted all iron 6276cc ohv V8 fed by four-barrel Carter carburettor Transmission Torqueflite three-speed automatic or four-speed manual Max power 325bhp @4600rpm Max torque 425 lb ft @2800rpm Construction steel box-section chassis welded to steel body Suspension: front independent, by double wishbones, coil springs, lever-arm dampers, anti-roll bar Rear live axle, dual-rate semi-elliptic leaf springs, Panhard rod, Armstrong Selectaride telescopic dampers Steering rack and pinion, Adwest Pow-a-rak optional Brakes Dunlop discs all round, divided circuits Length 15ft 8in Width 5ft 9in Height 4ft 5in Wheelbase 9ft 9in Weight 3697 lb 0-60mph 7.3 secs Top speed 137mph Price new £3743 (1967) Price now £10,000 (good) |

| Top: chromed Rostyles are a perfect match for Midlands bruiser. Left: chromed air filter housing was originally black. Below: practical tailgate to Jensen which has handy 16 cu ft of boot space. PowrLok limited-slip diff handles prodigious 4251b ft of torque |

| |

But it’s neither ergonomics or practicality that draws you in. Fire up the Interceptor and you’re in no doubt as to the origins of its engine. It could only be a blue-collar American V8. At idle, it’s vibration-free and practically silent. Flex the throttle and it’s loud, course-mouthed and hairy-nippled. With the big central selector lever in D, the car vigorously ushers off the line, changing up with full throttle at around 3500rpm, the V8’s timbre hardening with each increment. Acceleration is urgent and immediate, kickdown a hoot. Changes on the Torqueflite auto are largely heard rather than felt, being well insulated. Upshifts are always fluid and free of hesitation. When cruising, that large pushrod V8 is smooth and almost quiet with only the faintest hiss from the carb intake.

The ride is equally impressive, the adjustable dampers working overtime to iron out the ruts. Road holding is well balanced, too, cornering on wide sweepers being relatively neutral on a steady throttle. It’s only when you press on along twisty back roads that it goes horribly wrong. You probably could hustle the Interceptor. It changes direction well. It’s just that you don’t always want it to. And that’s largely due to the power-assisted rack-and-pinion steering that is fearfully buoyant at speed. It takes a lot of effort to counter the rapid self-centring action which is nerve jangling. Somehow you sense that should you so much as sneeze you’d soon be travelling northbound on a southbound carriageway. This is an adjustable set-up although most owners reckon that adjustments make little difference and you soon get used to the lightness.

The Ferrari has flaws too — just that they’re rather less elementary. From cold, the twin-cam 4-litre V12 is reluctant to start — a feature of pretty much any Maranello product of the era. When it does fire, it sounds glorious, a saturated surround sound of gurgling Webers, spitting exhausts and mechanical synchronisation. Initial take-off is hesitant and it’s not at its best pottering along in traffic but once on the open road the engine’s flexibility is a joy. Low-down tractability is unexpectedly generous and, past 4k, the engine note offers a welcome rush of blood to the head as the chains thrash, cams whine and those twin- chokes pop and gobble.

| Above: horses for courses; Ferrari may be the thoroughbred, yet Jensen is far from outclassed, particularly over bumps; great ride is one of Interceptor’s best features. Below: later Interceptors had full width grille, 330GTs single lamps — to Tjaarda’s chagrin |  |

|  |

At 3040lb, the 330’s no lightweight, and initial acceleration isn’t as strong as the Jensen’s yet it’s more than a match in the mid-range. Once warm, the four-speed ‘box remains slightly baulky, requiring short, positive throws although you’re constantly longing for an extra cog despite the overdrive on top (later cars had five-speeders) for more refinement at faster cruising speeds. Where the Ferrari really scores is where the Interceptor falls down. The old adage of when buying a Ferrari, you get the engine and the chassis is thrown in for free, doesn’t stack up here. While it doesn’t tide the bumps quite as well as the English car, body roll is always well contained and you can really attack corners. The steering is a revelation: always measured and precise. Turn in and there’s initial understeer giving way to benign neutrality. You can unstick the rear but it’s not happy there. Keep it clean and precise and this is a remarkably nimble machine for its size. All it lacks is great stopping power. It features the same anchor arrangement as the Jensen, but the Ferrari seems reluctant to stop cleanly, second guessing your resolve.

So the Ferrari is the better car then, the Jensen a mere try hard that’s out of its depth in the big leagues? Not really. They’re just different: polar opposites in the same orbit. Regardless of the badge, pedigree and any other nonsense, the 330 is a wonderful car in its own right that’s been oddly marginalised among marque devotees. The Interceptor is a hugely charismatic and capable mile-eater that’s great in a straight line and, dynamically at least, got better in time. As for the mongrel slur, it simply doesn’t matter whether its engine originated from Idaho or from down the back of a sofa: it works beautifully. And everybody loves a mongrel. •

Thanks to Keith Andrews and the Jensen Owners’ Club (01625 525699) and Spinning Wheel (01246451772) which is selling the Ferrari

Classic & Sports Car

Copyright 2003, Classic & Sports Car

Published with permission of Classic & Sports Car