| 330 GT Registry |  |

350GT vs 330GT 2+2

PRIDE&PREJUDICE

It was Ferruccio Lamborghini’s pride and Enzo Ferraris prejudice

— against his road car customers — that resulted in a supercar

battle that’s still being waged four decades Later

Words: Mark Dixon Photography: Matthew Howell

It's often said that the beet way to make a small fortune is to start with a large one. And in the same vein, the most surefire way to lose vast amounts of money is to have a go at building your own supercar. Sure, there have been some successes — Koenigsegg So when a tractor manufacturer with a sideline in commercial heating systems decided he was going to take on Ferrari at its own game, and play the game better, the odds were stacked against him. Remarkably, Ferruccio Lamborghini beat those odds and the supercar ‘great game’ is still being played more than four decades later. There’s a story that Lamborghini, a very successful industrialist by the early 1960s and a Ferrari owner himself, decided to set up in competition after he went to Maranello to complain about faults with his car and was kept waiting outside Enzo’s office for rather too long. It’s a good story but the more likely reality is that Ferruccio fancied the prestige of building supercars instead of tractors — and thought there was money to be made, too. |  |

| |

That wouldn’t have seemed such an outlandish concept in the early 1960s. Enzo Ferrari’s main interest then was in competition, and the road cars were basically cash cows to fund his racing ambitions. They were pretty and they were quick, but they weren’t particularly innovative or advanced, with single-camper-bank V12 engines and live rear axles. Ferruccio’s idea was simple: to build the best car in the world, bar none.

To do so, he set up a new state-of-the-art factory and gathered around him some key talent — engineers Giampaolo Dallara and Paolo Stanzani, and New Zealand mechanic and road-test troubleshooter Bob Wallace. And then there was Giotto Bizzarrini, like Dallara an ex-Ferrari man, but vastly more experienced; in fact, he had project-managed the 250GTO.

|

|

|  |

1966 FERRARI 330GT 2+2 |

1965 LAMBORGHINI 350GT |

‘Next to the 330, the Lamborghini is like a spaceship from another planet’

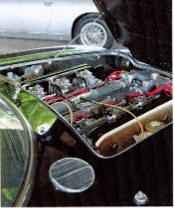

It was Bizzarrini who provided the heart of Lamborghini’s would-be supercar. Originally designed as a 1.5-litre, four-cam racing V12, it was scaled up to 3.5 litres and then detuned slightly for road use. It was an instant classic, and essential to Lamborghini’s fledgling reputation.

That reputation got off to a slightly shaky start when Lamborghini rushed out its 35DGTV concept car for the Turin show in late October 1963. Less-than-perfectly finished and with an odd juxtaposition of flowing curves and razor edges, it drew a mixed reaction. It also lacked an engine, the bonnet hiding a crate of ceramic tiles to weight the suspension, according to Bob Wallace.

Fortunately the production version, dubbed 350GT and launched in 1964, was significantly better. Carrozzeria Touring did a fantastic job of smoothing out and harmonising the car’s lines, and the car was a hit with road testers from the word go. They loved its powerful, smooth yet vocal-V12, and the fine handling that was aided by independent rear suspension — chalk one up to Lamborghini, since the equivalent Ferrari had an old-fashioned live axle.

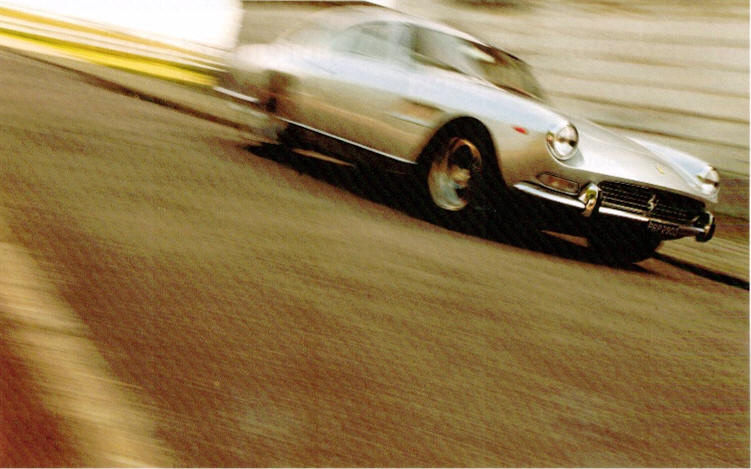

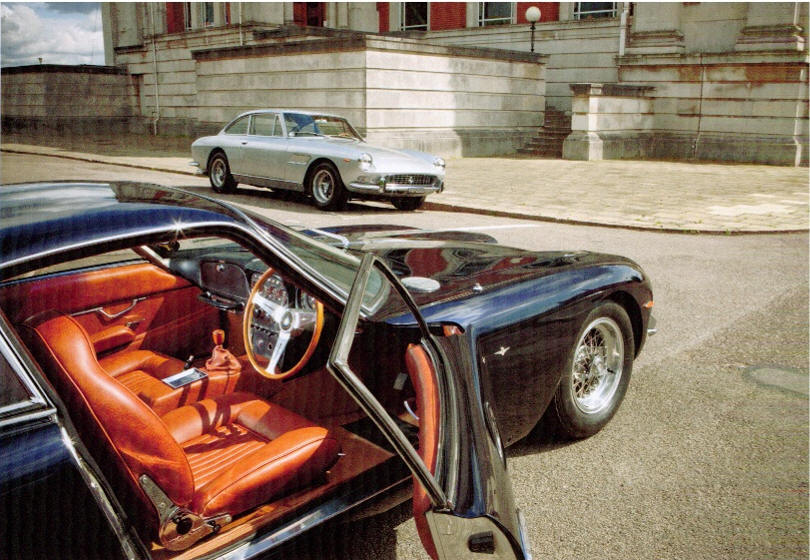

But what, exactly, was the opposition from Maranello? Price was the key. Yes, Ferrari brought out the 275GTB with IRS in 1964, but the closest equivalent to Ferruccio’s new car was the 330GT 2+2, an evolution of a 1950s design. And that’s what he have in our pictures, a 1966 Ferrari 330GT to compare and contrast with a 1965 Lamborghini 350GT. Similar in many ways, and yet so utterly different.

The Ferrari is a peach. Bought by Harry Metcalfe, editorial director of our sister magazine evo, at RM’s Maranello sale a couple of years ago, it’s a near-perfect example of a Series II 330GT. First-series cars had a twin-headlight front end, penned by Tom Tjaarda while he was at Pininfarina, but this was changed to a more conventional single-light style for 1965. Riding on deep-dish Borranis, it’s a handsome but understated car, which is just why Harry likes it. While not averse to a bit of supercar bling — indeed, he can often be seen exercising his Pagani Zonda — he appreciates the comparative discretion of the ‘60s Ferrari.

Next to the 330, the dark blue Lamborghini is like a spaceship from another planet. You’ll love or hate the ovoid headlights and the bubble- like glasshouse, with its noticeably curved side windows. The Octane team is firmly in the former camp, but there’s no doubt the 350 is more of a period piece than the Ferrari. This example was originally left-hand drive and supplied to UK Ferrari concessionaire Colonel Ronnie Hoare, presumably for comparison purposes with his regular stock-in-trade. Converted to RHD in the late 1960s, it’s a very low-mileage car that’s just crying out for more use.

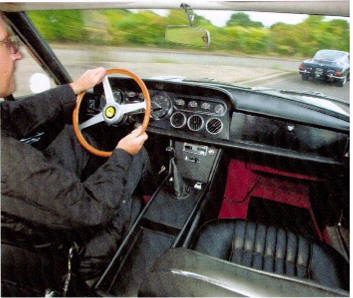

The Ferrari’s subdued style is carried through its interior, which is ‘60s minimalist, all straight lines and perfect circles. Uniquely, Harry’s car has a black Formica dash rather than the usual light tan-coloured wood, and it suits the car’s functional, office-like ambience. Only the pleated headlining strikes a note of rebellion — very rock’n’roll.

There’s no mistaking the supercar ambience inside the 350GT. Trimmed in what appears to be fake lizard, the cabin wraps around you like an aircraft’s. There are no rear seats, simply a luggage shelf with aluminium runners and a pair of stout leather straps to retain your Louis Vuittons. Oddly, the deep-cowled dials have stylised numerals that look very ‘50s and at least a decade older than the Ferrari’s clinically tidy, Letraset-like faces. Both cars have classical three-spoke, wood- rim wheels, although the Ferrari’s sits at a more bus-like angle — something you soon forget about on the move.

Harry Metcalfe believes cars are to be used, so his 330 is properly sorted. Flashing down the M4 on the way to our photoshoot, the silver Ferrari easily holds its own in the outside-lane rush of clenched-teeth commuters. It’s a civilised high-speed cruiser, its Colombo-designed V12 sounding unusually subdued for a Ferrari, displaying little of the cam thrash/chain whir/carburettor roar that journalists are fond of wittering about. Put your foot down and the motor does not yowl, neither does it exactly hum: instead there’s a turbine-like, hard-edged whoosh that’s appropriate to a GT car, if not so exciting for an adrenaline-hungry petrolhead.

Taking the long way home, the Ferrari acquits itself well on challenging B-roads too. The ride is pretty decent and only the occasional slight skip sideways over a mid-corner bump betrays the live rear axle. You need a bit of commitment to heft the steering wheel into a corner but the weight quickly lessens as the car adopts its attitude, and there’s good precision to be found. The brakes are fantastic, hot or cold.

Our drive in the Lamborghini was frustratingly brief, in comparison, but just enough to hint at the newcomer’s potential. That Bizzarrini V12 has a touch more menace about it, developing a trace of snarl over 4000rpm, and there’s no doubting the superiority of the independent rear suspension. The five-speed gearbox — Ferrari didn’t switch to a five-speeder for the 330 until after the 350GT appeared — has a heavy but positive action, and the less-assisted brakes need a harder push than the Ferrari’s. The steering is at least as good as the 330’s and has a phenomenally and quite unexpectedly good lock: we’re talking London taxi turning circles here.

With both cars offering similar performance figures, the choice is not an easy one. The Ferrari feels a lot more spacious inside and is a genuine two-plus-two; more so than, say, today’s Aston DBS or Lotus Evora. Its more conservative Pininfarina lines have also aged more gracefully.

But the Lamborghini is more exciting. It trades a little practicality for increased visual drama, a little function for rather more form. Ferruccio Lamborghini, who was determined that the 350GT should undercut Ferrari significantly on price, is also reckoned to have lost maybe $1000 on every one he sold. That surely, is the clincher: the 350GT is a proper supercar.

Thanks to Harry Metcalfe for the loan of his 330GT, and to Coys of London, www.coys.co.uk, for supplying the 350GT, which is for sale. Thanks also to the volunteers at Kempton Park Water Works heritage project, www.kemptonstearn.org.

© 2009 Dennis Publishing Limited