| 330 GT Registry |  |

|

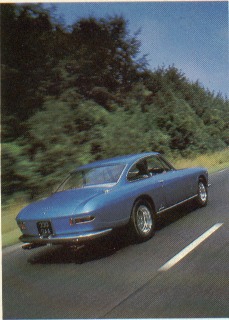

The only Ferrari bargain known to man, the 330GT is a large, fast and imposing two-plus-two with a poorer name than it deserves, reports Gavin Green, after |

Horse With No Name

Bill Branton does not look like your average Ferrari owner, even though he owns your average Ferrari. A maintenance foreman, Branton lives on a housing estate in Basingstoke, and for normal daily transport uses a beaten-up blue Escort van. He does not wear Gucci shoes, gold bracelets or tailor-made shirts; his accent is more Kennington than Cambridge. He does all maintenance work on the Ferrari himself (‘it’s really quite simple’), and his Prancing Horse’s corral is a tiny garage in front of his house, rather than a spacious workshop.

The Branton machine is also a Ferrari more for the common man than the collector. The 330GT has never been coveted, or loved by Ferrari aficionados. It’s too big, too unwieldy, too ugly, so the experts say. And besides it’s a four-seater — a breed of Prancing Horse which is never as desirable as two-seaters or convertibles. In short, if you want to get into a Ferrari saddle, you won’t do it much cheaper than a 330GT.

‘I bought it because it was the only Ferrari I could afford,’ says Branton. ‘I wanted something out of the ordinary. I had a look at a lovely Aston Martin DB4, and went for a drive. But it felt like a tank. I really wanted a Dino 246, but it was hard to get a good one at the right money. The 330GT came along, at £10,000, four years ago. I bought it. It has not missed a beat.’ The previous owner was an eight-month-old girl. ‘Her father bought her the car as a christening present-cum investment,’ says Branton. ‘I believe she now owns a Ferrari Boxer.’

Thanks to its immaculate condition, Branton’s 1965 330GT Mk1 is now probably worth about £13,000. You can get 330GTE much cheaper, though. Ferrari distributors, Maranello Concessionaires, tell us such a machine in good rather than concours condition would sell for about £8000.

For that you will get a distinctive rather than dainty machine which will turn more heads at the pub than any £8000 Sierra or Cavalier, and a car which goes like no new £8000 car on the market. The 3976cc single overhead cam per bank V12 runs effortlessly and smoothly to its 6600rpm redline (at which point maximum power — a claimed 300bhp — is also produced). Maximum speed is a true supercar-like 150mph (cruising at 110-120mph is effortless, with the V12 growling contentedly in its flick switch-operated overdrive top), while 60mph comes from rest in about 7.5sec (much quicker than any normal 1984 tin-box).

As a Grand Tourer Enzo’s used car for the masses is particularly at home on the high way. Not long after I introduced my Levi-clad rump to the 330GT’s leather-clad bucket, we were cruising down the M3 between Basingstoke and the A303 turn-off. High speed stability was exemplary; big revs were being shown on the huge Veglia tachometer, and there was that unmistakeable Ferrari growl coming from the nose, but overall noise levels were low. The ride, rock hard at first — due to the cold dampers — had taken on an impressively suppleness.

As a Grand Tourer Enzo’s used car for the masses is particularly at home on the high way. Not long after I introduced my Levi-clad rump to the 330GT’s leather-clad bucket, we were cruising down the M3 between Basingstoke and the A303 turn-off. High speed stability was exemplary; big revs were being shown on the huge Veglia tachometer, and there was that unmistakeable Ferrari growl coming from the nose, but overall noise levels were low. The ride, rock hard at first — due to the cold dampers — had taken on an impressively suppleness.

Onto the A303, and off in search of some winding back roads. The handling is good — your first fast corner is enough to prove that. The steering is too heavy and rather woolly — but the chassis competence is enough to ensure a pleasing responsiveness. The brakes too — four solid discs — are also heavy to operate and so is the clutch. It’s a man’s car, this Ferrari. Your first couple of miles of 330GT motoring are also enough to show the inadequacy of the pedal positioning. The pedals are extremely large and close together (left foot brace and all) — and are crammed into a footwell which is simply too claustrophobic for an average pair of size nines. To make matters worse there is a nasty ridge on the top of the footwell; I had to change my tennis shoes, which have seen good service in many a supercar, for a pair of tight fitting and narrow leather covers which Branton keeps in the boot of the Ferrari. You need narrow shoes, without ridges, to drive this car thanks to that footwell,’ he says.

At close to 16ft long, 330GT |

|

The small, dainty gearlever, which sits in front of a large ashtray with the twin flags of Ferrari and Pininfarina (the body’s designers and builders) etched on its lid, also has an action which takes some familiarisation. There is a good deal of linkage play and the change itself, though light and easy, is rather slow. This four-speed (with flick switch overdrive) gearbox was built in the days when you bought a Ferrari for the engine and got the transmission free.

But as you motor along a winding road, with owner Bill Branton bracing his legs a little harder against the passenger footrail as the speed increases, you cannot help but be impressed with the agility of Ferrari’s 15.9ftlong, 30421b heavyweight. The controls may take some getting used to, and the gear change may be slow, but it’s obvious that the breeding is here. On tight roads is more prancing than ponderous. The car can be swung quickly from corner to corner, the engine response is excellent and the roadholding limits are high. You may have to spin the big wood rimmed three-spoke steering wheel around like the tiller on a paddle steamer; and the brakes will soon start to fade if you push hard — but it is clearly a Ferrari. The car turns into bends obediently. Push harder and the nose starts to take on some altitude. Force even harder and the front rubber will start to scream as the 330GT adopts a gentle understeering posture. It’s no Daytona or 275GTB, that much soon becomes clear. But it’s still more sporty than sloppy.

The 330GT — which replaced the 250GTE 2+2 in 1964— got off to a bad start with the aficionados and the press straight after its launch. Unveiled at the Maranello press conference early that year, the 330GT received a much more mixed reaction the magazines than any of its predecessors. It was the rather bulbous looks which did the damage. And, although it sold well (625 were made in its l8 months production run). Ferrari and Pininfarina had seen the error of their ways: a more conventionally styled 330GT, the Mk2, was released in mid-1965 with the four headlamp styling replaced by single lamps integrated into the front wings.

Styling apart, in most ways the 330GT Mk1 was typical of its predecessors. The chassis was made from electrically welded steel tubes of oval ‘section. Front suspension was by wishbones, with coil springs and an anti-roll bar; the front wheels were manipulated by a worm and peg steering system. At the rear there were semi-elliptic leaf springs locating the live axle; adjustable Konis replaced the more prosaic rear dampers fitted to the 250GTE 2+2 (Ferrari’s first four-place car). Like all Ferraris before (and in fact most since) the chassis was crude. But there was a certain composure a civility about it which made it a fine car on the twisty stuff, and over bumps.

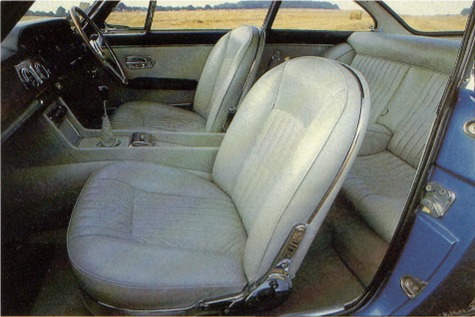

Inside, the Ferrari is also a civilised machine. True to its touring, rather than sporting, nature there is a generous amount of woodwork adorning the dash and leather about the cockpit. The quality of the body work, too, is impressive, unlike some

Ferraris (in which the clothes were often lashed together to adorn the raison d’etre for the machine, the engine). But like all Ferraris, the instrumentation is comprehensive. And like all Ferraris the starting technique must be practised before you first try to tempt the V12 into life. You must switch on the electric fuel pump (the powerful tick, tick, tick wanes when the carburettor is primed), and then push the ignition key turn it) to tempt the crankshaft out of its languor. You have to be quick on the accelerator when the engine catches.

|

|

Ferrari also fixed the cramped rear seat room of the 250GTE when they launched the 330. Rear room is not capacious — this is, after all, a Ferrari not a limousine — but it is surprisingly generous. A man of average height would find his knees kissing the back of the front seat, and his hair brushing the roof lining — but he could travel a reasonable distance, in comfort, in the back of the 330. The front seats, too, are comfortable. The squabs may be short on height, but the chairs are not short of support.

Ferrari also fixed the cramped rear seat room of the 250GTE when they launched the 330. Rear room is not capacious — this is, after all, a Ferrari not a limousine — but it is surprisingly generous. A man of average height would find his knees kissing the back of the front seat, and his hair brushing the roof lining — but he could travel a reasonable distance, in comfort, in the back of the 330. The front seats, too, are comfortable. The squabs may be short on height, but the chairs are not short of support.

Bill Branton drove back to his Basingstoke home. He clearly likes his steed, but he does not treat it with needless reverence. He drove it home hard. Redlining the V12 in the gear (the Colombo V12 feels and sounds as though it could go higher than its 6600 limit),’ pushing it hard into the bends, working the brakes and gears. ‘I took it to the Monaco Grand Prix and back just after I bought the car. I had some doubts about undertaking such a long trip in an old car— but the Ferrari proved excellent. We cruised at high speed, had no problems, and averaged 17mpg. I don’t use the 330 a lot — I’ve done 9000 miles since I’ve had it, mainly on sunny weekends — but when I do drive the car I like to exercise it. I really do believe it is a very good vehicle. It is not a problem to look after; and has not proven expensive.’

It is no Daytona, of course. It is not as fast nor as beautiful nor as nice to drive. But then you can persuade a 330GT Mk1 to live with you for about a quarter of the price. Many — those without Bill Branton’s mechanical skills — might wince at the running costs (just as much as those of the Daytona which is a much better investment, should such a thing matter). Others may dislike the shape. But few will object to the big Prancing Horse on its yellow shield which stares at you from the steering wheel boss; and few will object to the noises emanating from the four tailpipes. Few will object to the lovely engine with its black crackle finished cam covers and air cleaner. Surely such ingredients, for such money, constitute a bargain.

SUPERCAR CLASSICS

And when the motor does catch there us the unmistakable Ferrari bark of the engine first igniting, and the powerful thrash of the cam chain being spun frenetically around its course. You listen, carefully, for that other audible giveaway of Ferrari propulsion power — the hiss of the carburettors. But they seem strangely muted. It must be the size of the air filter, you conclude — and the Fact that this Ferrari has only a trio of Webers rather than the sextuple which classic Ferraris use. Give the right pedal a poke before clutch engagement (like all Ferraris the 330GT has a lightweight fly wheel; be parsimonious with the revs and the flywheel quickly loses it momentum), let out the heavy left pedal, and Bill Branton’s beast from Basingstoke moves off, accompanied by a background of chain thrash and gear whine. These noises — redolent of all Ferraris — can be tolerated, and even enjoyed. But the slight vibration transmitted to the bodyshell at low to medium engine speeds cannot. Check the history books and you’ll see that the engine mounts were changed when the 330GT Mk2 appeared:

And when the motor does catch there us the unmistakable Ferrari bark of the engine first igniting, and the powerful thrash of the cam chain being spun frenetically around its course. You listen, carefully, for that other audible giveaway of Ferrari propulsion power — the hiss of the carburettors. But they seem strangely muted. It must be the size of the air filter, you conclude — and the Fact that this Ferrari has only a trio of Webers rather than the sextuple which classic Ferraris use. Give the right pedal a poke before clutch engagement (like all Ferraris the 330GT has a lightweight fly wheel; be parsimonious with the revs and the flywheel quickly loses it momentum), let out the heavy left pedal, and Bill Branton’s beast from Basingstoke moves off, accompanied by a background of chain thrash and gear whine. These noises — redolent of all Ferraris — can be tolerated, and even enjoyed. But the slight vibration transmitted to the bodyshell at low to medium engine speeds cannot. Check the history books and you’ll see that the engine mounts were changed when the 330GT Mk2 appeared: